Chapter 6:

Whereas the preceding chapters concerned the developmental sequence of syntactic structures, this chapter primarily attempts to bring together all the constructions that students need in order to explain how any word in any sentence is related to the basic sentence pattern. The constructions and concepts are introduced in the order in which they should be taught, an order that does not differ whether the approach is spread over grades 3-12 or crammed into a single college semester. Chapter Seven will discuss such matters as at what grade level concepts might best be taught and with what kinds of exercises. In my college grammar course for teachers, students work with complete essays, usually written by their peers. In the first essay, they look for all the prepositional phrases, in the next they look for prepositional phrases plus subjects, finite verbs, and complements. With each essay, new constructions are added in the order in which they are presented here. Somewhere, I believe it is in Archaists and Innovators, the Russian Formalist Yuri Tynianov describes a theory as a mental device for holding and organizing scattered bits of information. He does not suggest that a theory has to be all-inclusive, nor is he particularly worried about "exceptions." Tynianov, like the other Russian Formalists, considered himself primarily an "innovator": he was charting new territory. As such, he had to get a basic understanding of the lay of the land -- until he had a general orientation, he couldnít worry about all the specific exceptions or details. Unfortunately, we frequently forget that students are usually in a position similar to Tynianovís -- what they need is a general map of the rules of syntax. Without it, they will not have a conceptual framework within which to place specific details and exceptions. How many students, for example, understand (or care) when Paul Roberts, in Understanding English -- a text for high school students--, devotes half a page to the question of whether "moving," in "moving van," should be considered a participle or a regular adjective. The question is interesting, vital, and perplexing -- to a structural linguist. But how many students use "moving van" incorrectly? What Roberts has done, of course, is to bring into his high school textbook a question that he discussed with graduate students and fellow linguists. But to take this approach -- to deal with problems and exceptions -- is like teaching life-saving: it is effective only if the student already knows how to swim. The theory that students need to know is really very simple. It is the syntax of Jespersen and Curme, minus the complicated problems, and slightly modified by insights from modern linguistics. We must continually remember, however, that students are approaching syntax from a position exactly opposite that of Jespersen and Curme: they were masters. Their grammars are, so to speak, dissections of syntax, breaking it down into the smallest pieces so that they could find and analyze all the exceptions, all the rules. Students, coming from the other direction, need an integrating theory -- they have to be able to put the pieces together so that they can see how the whole system works. They need a theory that will help them analyze and understand the complicated sentences that they read and write. It is such a theory that this book attempts to present. THE BASIC PRINCIPLES OF THE THEORY English has one basic sentence pattern: Subject/Verb/(Optional Complements). The optional complements create four main variations of the basic pattern: The basic principle of this entire theory is that: with the exception of interjections, every word in every sentence either occupies a position in the basic pattern or is related to the pattern through modification. Studentsí objective in studying the theory is not to memorize and regurgitate definitions, nor simply to be able to recognize constructions, but rather to be able to explain how any word in any sentence is related to the basic pattern.1. Subject/Verb Nexus and Modification As we saw in Chapter Two, syntax involves primarily two kinds of relationships, nexus and modification, nexus being the adhesion of the basic sentence parts, modification being the expansion of those parts through the use of adjectives and adverbs. In an interesting, but little known textbook called How Thinking Is Written, Lawrence Hall clarifies this concept of syntax still further by discussing what he calls "the four grammatical relations": case, modification, reference, and tense/mode. His distinction is important because, if we wish to teach systematically, we must realize what goes with what. Without doing too much violence to Professor Hallís concepts, we can equate his "case" with nexus, and his "modification" with ours. But his last two categories indicate what, in a theory of syntax, we are not concerned with. Tense forms and modals are a different kind of relationship, important, but distinct from syntax as it is here defined. Likewise, reference is distinct from modification. As Professor Hall states: The reference relation is of vital importance in language because it is a means of establishing clearly the identity of things talked about. It exists only between pronouns (or words with pronoun or reference characteristics like "accordingly") and the things to which they are references or indexes. No other part of speech may be said to refer to another part of speech. We may not speak of a noun to which an adjective refers. We must speak of a noun which an adjective modifies. (118)The passage sounds a bit didactic, and I must confess to asking students what an adjective "refers to," but the distinction is important. There are numerous systems in language that operate simultaneously. But in studying a system, we should exclude, as much as possible, the others, just as scientists, studying the properties of heat, do so in a laboratory to exclude as many non-desired variables as possible. For the study of syntax, students need not distinguish between nouns and pronouns. The Mechanics of Analyzing Passages Our approach to syntax differs from the traditional in several ways, one of which is that the studentsí objective is to explain how every word in every sentence relates to the basic pattern. In many traditional exercises, for example, students are given a set of sentences and are asked to identify only the noun clauses or the direct objects or the infinitives, etc. which they then list on numbered paper. But if students are to analyze entire sentences, they need some easy means of visualizing the various parts. Sentence-diagramming accomplished this, but at a price -- students had to remember all the rules for which line goes where, and they had, in effect, to recopy the entire sentence. None of this is necessary. Students can work with typed, double-spaced paragraphs or short essays and make all of their notations right on the page without recopying a single word. The only notational "rules" they must learn are: 1.) Place parentheses around prepositional phrases and draw an arrow to the word that each phrase modifies.As we will see, these "rules" will highlight the main parts of the sentence and visually group the prepositional phrases and subordinate clauses. Many of my students prefer additional visual markings, so we have developed the following additional "rules" for those who wish to use them: 4.) Circle infinitives and label their function.By avoiding the diagrams of diagramming, students are able to focus more of their attention on the actual syntactic analysis. The Eight Parts of Speech: Concepts not Categories The concepts of nexus and modification should be connected with the studentsí study of the parts of speech. The traditional eight (nouns, pronouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, and interjections) are fully satisfactory, indeed necessary, for helping students reach their objective, if they are taught as a means to an end and not as an end in themselves. The current disdain for the eight parts of speech results from their having been taught as ends in themselves. Students were asked to memorize definitions (A noun is the name of a person, place or thing.), but were rarely, if ever, invited to use the parts of speech as concepts to analyze sentences. Although teachers will probably use definitions to help students learn to recognize parts of speech, the students have no need to memorize definitions. What students need to be able to do is to look at a word in a sentence and state that it functions as a noun, verb, etc. Students already have these categories in their heads. They do not say or write "She ined it." They use "in" as a preposition and only as a preposition. If they are to analyze sentences, and to explain or discuss their analysis, they need simply to relate the labels of the eight parts of speech to the categories that are already in their heads. They can develop these connections inductively. For example, having worked with a list of prepositions, they can learn that any word that answers the question "What?" after a preposition functions as a noun. Syntactically, there is no reason for students to learn the subspecies of most of the parts of speech (proper nouns, personal pronouns, linking verbs, etc.). The pedagogical problem with the eight parts of speech is that they have been taught deductively, rather than inductively. The distinction is crucial, since it helps explain why traditional grammar has been so difficult for students and so ineffective in improving their writing skills. If we oversimplify a bit, we might visualize the first "grammarians," attempting to compile a grammar. As they looked at sentences, they noted that certain words functioned as subjects and objects. Other words modified or explained these words. They labeled the first group "nouns"; the second, "adjectives." We cannot be certain, of course, but it seems highly probable that they arrived at their categories inductively. As a result, they arrived at a rule which states: "Adjectives modify nouns or pronouns." Pedagogically, however, we have reversed that sequence: we teach the rule first, as if it ontologically precedes the process that resulted in its creation, and we totally omit the process of induction. This reversal creates severe problems for students, who look at an isolated word, attempt to determine its part of speech, and then deduce its function. One need only think of the word "like," with its many possible meanings and functions, to realize that the reversed process can lead to endless frustration. A pedagogical theory of syntax should be based on function in the sense that the part of speech of a word is determined by its function in a sentence. Instead of first determining the part of speech of a word and then looking for its function, students should look at the function of the word and thereby determine its part of speech. Obviously, students will need some help: we cannot expect them to start from scratch and arrive at the theory. We can, however, assist them through "guided induction," a term suggested by Robert Carey and John Bolton at Montgomery College. The traditional simple definitions, examples, little "rules" (Whatever answers the question "what" after a preposition is a noun or pronoun.), all can help the student make the initial connection between the label for the concept and the category that is already in her head. Traditional grammar, since it focused on the individual word, underemphasized the fact that "parts of speech" are concepts, not categories of individual words: syntactic constructions (prepositional phrases, subordinate clauses, verbals, etc.) can all be seen as fulfilling a function as a part of speech. Prepositional phrases, for example, "always" function as either adjectives or adverbs. The concepts of the parts of speech, therefore, should include not just words, but also constructions. ***** It is time for a confession: I lie. And I believe that all teachers should do likewise. Prepositional phrases do not always function as adjectives or adverbs: 99% of them do. The other 1% function as interjections or nouns. I cannot, however, see any justification for confusing students by telling them the whole truth. Millerís concept of short term memory and the magic number seven (See Chapter Eight.) even suggests that the whole truth may do more harm than good. We can see how this might be so if we imagine what a student is doing as he studies prepositional phrases. The student has in front of him an essay and a list of words that usually function as prepositions. The student has to find the words on the list in the essay. Having found one, the student must ask the question "what?" after it, and then check to see that whatever answers the question cannot be a sentence by itself, i.e., that it is not a subordinate clause. If the "preposition" is the word "to," the student must remember that if the word that answers the question is a verb, the construction is not a prepositional phrase. Having determined that a phrase is indeed prepositional, the student must next find the single word outside the phrase that the phrase modifies. He must also remember that if the word modified is a noun, the phrase is an adjective; if the word is a verb, adverb, or adjective, the phrase is adverbial. For most teachers, this is all very easy and obvious, but for the novice, it is not. It is, indeed, a lot to remember. Why, then, should we add still another thing for the student to remember, i.e., that 1% function as exceptions, when the student will only find such exceptions in one phrase out of 100? As noted in Chapter Three, students should repeatedly be told that they are expected to make mistakes. The 99 correctly attributed phrases will help the student assimilate the concept, and, when the student has learned about interjections, he will be able to see prepositional phrases that act as such. His early "errors" will be the same as the childís "I cutted" or "I readed." Such pedagogical "lies" are an important aspect of this approach, mainly because of interjections, but also with such things as retained complements (See below.). ***** In my grammar course for teachers, I usually spend only about fifteen minutes on an introduction to the parts of speech, primarily because I like to give students a conceptual "map." But it is not necessary to begin with the parts, and indeed far too much time is usually spent on them in most grammar classes. The parts can be introduced as they are needed: there is, for example, no need to introduce subordinate conjunctions before students study subordinate clauses. The following discussion is thus much more detailed than any I give to students, but I have decided to include it because of the derision with which the parts of speech are often met. Ken Donelson, for example, the influential editor of English Journal, scorned the teaching of grammar in an editorial in which he relates a conversation he had on a plane: "(What do you wish you had learned?)That Donelson sees these definitions as "stupid, pointless, valueless," simply indicates that he does not know what to do with them: likewise, a Siberian peasant might consider a computer. But as we will see, the eight parts of speech do have pedagogical value. Nouns and pronouns Words or constructions which serve a nexal function (subjects, direct and indirect objects, predicate nouns) or as objects of prepositions are nouns or pronouns. A few additional constructions, discussed below, also require nouns or pronouns. Adjectives Words or constructions that modify nouns or

pronouns are adjectives. The nexal pattern, S/V/PA, emphasizes such modification:

"The boys are foolish" as opposed to "the foolish boys." Much energy has

been wasted in debates about such things as whether "city" in "city hall"

is an adjective or a noun functioning as an adjective. If students wish

to consider it a noun, there is no reason why they shouldnít, even though

it violates my theory. The important thing is that in a sentence such as

"Someone burned city hall" the students realize that "city" goes with "hall"

and not with "burned." Likewise there is no syntactic problem with studentsí

considering a possessive noun "Maryís football" as a simple adjective.

The studentsí objective is not to learn the names of all possible constructions

but to see how words relate to each other.

Verbs Verbs must be divided into two categories. Words which fill the "verb" slot in a sentence pattern have a nexal function and are called "finite." Any verb that does not fill such a slot has to be a verbal -- a gerund, gerundive, or infinitive. As we will see, verbals are "verbs" that fill non-finite-verb functions. The "particle" additions to many verbs ("turn on," "run up") create endless difficulties for the professional linguist, difficulties which can and should be avoided in the classroom. Students should have the option of considering the "particle" as either part of the verb itself or as an adverb modifying the verb. Adverbs Words or constructions that modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs are adverbs. Prepositions A relatively small group of words function to connect a noun or pronoun to another word or construction in a sentence. The prepositional phrases created by prepositions function as modifiers. Conjunctions Conjunctions, like verbs, have to be divided into two groups, depending on their functions. Coordinating conjunctions (primarily "and," "but," and "or") join equal words or constructions -- noun and noun, prepositional phrase and prepositional phrase, etc. Subordinating conjunctions connect a subordinate clause to a word or construction in another clause. As we will see, subordinate clauses "all" function as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs, i.e., they too can be analyzed in terms of their nexal or modification function. (This is, of course, another pedagogical lie.) Interjections Words or constructions that are not related

to the sentence pattern but rather express the speakerís or writerís attitude

toward the information conveyed in the sentence are interjections. Interjections,

in other words, denote those words and constructions that have neither

a nexal nor a modification function. Most traditional texts concentrate

on words ("oh," "well," "gee-whiz") and ignore the frequent use of constructions.

In "He wanted, to tell the truth, to ask you to marry him," "to tell the

truth" is an infinitive construction used as an interjection.

THE CONSTRUCTIONS AND CONCEPTS

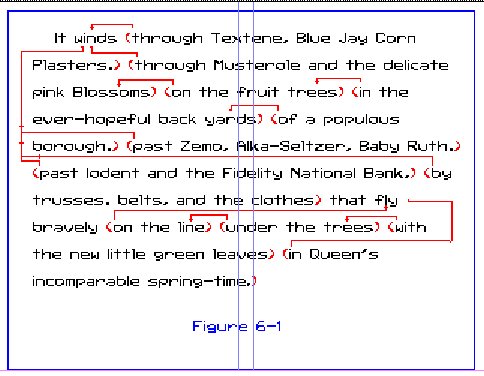

Compounding, ellipsis, and Prepositional Phrases Having claimed that the pedagogical sequence follows the sequence of natural development, I have some explaining to do to justify putting these three concepts first. Infants do not begin to speak with prepositional phrases, compounding and ellipsis. But we are not attempting to teach infants to speak. As was noted in the previous chapter, children have a basic mastery of at least 80% of syntactic constructions before they enter kindergarten. Our objective, rather, is to help students gain a conscious mastery of these constructions -- as we will see, there are several reasons for violating the natural order at the beginning of the process. Compounding Many traditional texts deal with compound subjects, compound verbs, compound objects, compound sentences, etc. This approach not only needlessly complicates an introduction to syntax, it also implies that some things can be compounded whereas others cannot, an implication that is not true. Conceptually, compounding occurs when two or more of the same construction or part of speech function identically in relation to another word or construction. Any construction can be compounded. Students who understand the concept of compounding will be able to identify compound verbs, compound sentences, or compounds of any other kind without having to be specifically told that such compounds exist. Ellipsis The traditional emphasis on categorizing words explains why so little attention has been paid to the concept of ellipsis -- out of sight, out of mind. But ellipsis, the omission of words that are logically understood, is an easily learned concept that can simplify many syntactic explanations. In "Come in," for example, "in" is a preposition, the object of which has been ellipsed. The ellipsed object is understood as being whatever the speaker is in. Ellipsis allows us to eliminate such traditional categories as subjective and objective complements. In a sentence such as "They made Mary president," "Mary" can be explained as the subject, "president", the predicate noun, of the ellipsed infinitive "to be." The infinitive construction functions as the direct object of "made." This explanation not only uses fewer categories than does traditional grammar, it also more closely coincides with what modern linguists have shown to be the structure of the language. Ellipsis is also the studentsí means for explaining many reductions. As we saw in the preceding chapter, reductions are a primary characteristic of mature writing; later in this chapter we will see how students can use the concept of ellipsis to understand and explain many connections by restoring the reduction to a simpler form. Prepositional Phrases A primary reason for beginning with prepositional phrases is that they are easy to learn. Since prepositions are few in number, students can be given a list such as the following and be asked to place parentheses around every prepositional phrase, and to draw an arrow to the word modified, in a paragraph or short essay. about, above, across, after, against, along, among, around, as, at, before, behind, beneath, beside, between, beyond, by, despite, during, except, for, from, in, inside, into, like, near, of, off, on, onto, outside, over, since, through, to,* toward, under, until, up, upon, with, within, without, aside from, as to, because of, instead of, out of, regardless ofWith no other construction can students so easily take a relatively short list of words as an aid. Having found a word on the list in their passage, they next form a question with that word followed by "what," i.e., "since what?" If whatever in the sentence answers that question forms a sentence of its own, the construction is not a prepositional phrase:"but" when it means "except" Another reason for beginning with prepositional phrases is that they account for so many syntactic connections. Here, for example, is how E.B. White describes the road to "The World of Tomorrow": It winds through Textene, Blue Jay Corn Plasters; through Musterole and the delicate pink Blossoms on the fruit trees in the ever-hopeful back yards of a populous borough, past Zemo, Alka-Seltzer, Baby Ruth, past Iodent and the Fidelity National Bank, by trusses, belts, and the clothes that fly bravely on the line under the trees with the new little green leaves in Queensí incomparable springtime.Figure 6-1shows the same passage with the prepositional phrases marked. Admittedly, this sentence is exceptional: sixty of its sixty-five words are in prepositional phrases. My research indicates that the norm for professional writing is 38%, not 92%.

But the norm is impressive enough! Consider it from the studentsí point of view: we have given the student the objective of explaining how all the words in any sentence relate to the basic pattern. Before she starts, she sees a page of words and can explain none of the syntactic connections. But having learned one construction, she can now account for 38% of the connections. Actually, she can account for more than that since she can not only group the words inside each phrase but also relate each phrase to a word outside it. Students can literally see themselves making progress, and this self-perception of their own progress may be the single most important aspect of this entire approach. Traditionally, students have found themselves at sea amidst a storm of rules and exceptions, with no goal or end in sight. Can they be blamed for losing interest in the game? In this approach, on the other hand, they know exactly what their objective is, and they can see how far they have progressed toward it. Nothing breeds success like success. Whiteís sentence illustrates still another important principle of the theory, the rule of ALTERNATIVE EXPLANATIONS. I have marked "under the trees" as modifying "line," but could we not justifiably say that it modifies "fly"? Since we could delete "line" from the sentence and keep "under the trees" ("that fly bravely under the trees"), the adverbial explanation is just as good as the adjectival -- both explanations are equally correct. Students often balk at this principle -- they want the right explanation, and donít appreciate having more than one. But life isnít that simple. It is particularly important that teachers be open to the principle of alternative explanations, since some students will tend to view a construction one way; others, another. The teacherís job is to help students develop a sense of syntax, not to impose their own theory on students. With its numerous compounded objects of prepositions, Whiteís sentence also illustrates why I introduce the concept of compounding in the process of studying prepositional phrases. We need another example, however, to see the value of the concept of ellipsis. In analyzing sentences that have compound objects of a preposition, students frequently find it helpful to consider a single phrase as two phrases with the second preposition ellipsed: Every week she wrote to her mother, who lived in France, and her sister, who was in California.Many students feel uncomfortable placing parentheses around "her sister" when there is no preposition with it. The concept of ellipsis thus allows them to insert the preposition (Asterisks denote ellipsed words that have been inserted.): Every week she wrote (to her mother,) who lived (in France,) and (*to* her sister,) who was (in California.)My college students also use ellipsis to explore how prepositional phrases are often reduced to adverbs: In contrast to the bright lights on stage, the dimly lit rooms beneath were filled with relics of previous plays."Beneath" is rightly considered an adverb, but how does it connect with the rest of the sentence? First of all, it is a reduction of "beneath the stage": that is what it means. Having restored it to a prepositional phrase, we could say that the phrase functions as an adjective modifying "rooms." Or, applying the principle of alternative explanations, we could go further with the restoration: "the dimly lit rooms beneath *the stage*" is a reduction of "the dimly lit rooms *which were* beneath *the stage*." "Beneath" is an adverb modifying the ellipsed "were" in the clause that modifies "rooms." Ellipsis with prepositional phrases is just one illustration of how this approach to syntax invites, or I should say "forces," students to put on their thinking caps. Ask a class to analyze the preceding sentence, and at least one student will mechanically mark "on their thinking caps" as a prepositional phrase. If this student has the bad luck to be called on in class to explain the sentence, and no one questions the explanation, I ask if that is what the sentence means. In response to the blank stare that my question usually evokes, I amplify: what is it that the students are supposed to put "their thinking caps on"? Isnít to consider this as a prepositional phrase the same as considering "put it on the table" a prepositional phrase? Students quickly get the point -- the sentence means that they should put their thinking caps "on *their heads*." A similar thought process is involved in their distinguishing between: The ease with which they are learned, and the

number of syntactic connections for which they account are two of the reasons

for beginning with prepositional phrases. The third reason involves studentsí

perception of subjects and verbs.

BASIC SENTENCE PATTERNS What is the subject of "Some of the men were angry"? If we use our common sense, the answer is obvious: the subject is "men." Who were angry? Men. For years students have been using their common sense to give what is, semantically, a correct answer, only to find themselves frustrated by the teachersí refusal to accept it. Those of us who have been initiated into the game of syntax, with its rules, immediately perceive that the subject is "some," but nobody has bothered to initiate the students into the game. Even many of my students who have had excellent training in traditional grammar have never heard of the simple rule: A subject and verb can be inside a prepositional phrase (rarely), or it can be outside, but it can never be half in and half out.And with this rule I am not lying: it holds absolutely. One of the reasons that students should start by learning to identify all of the prepositional phrases, therefore, is that they can then exclude all such phrases when they are looking for subjects and verbs. This rule, which tells them why "some" and not "men" is the subject of our example, is itself an example of another principle, the principle of exclusion. The principle of EXCLUSION is quite simple: If something is X, it cannot also be Y. If a word is the object of a preposition, it cannot also be the subject of a verb. If a word is the complement of one verb, it cannot be the subject of another. We will see more examples of the principle of exclusion, but note how the latter rule helps students. It is not unusual for a sentence such as the following to be on the board: They were watching the train that was passing. Students have little trouble identifying "they" as the subject of "were watching" and "was passing" as a finite verb. But what is its subject? Many students respond "the train." The principle of exclusion helps them see why "the train" cannot be the subject -- that "that" has to be. Examples such as this one also make students believe that the rule is inherent in the language and not just something the teacher made up. None of them would say or write: "They were watching the train was passing." Every student would put the "that" in the sentence. Why would they do so? There is only one reason: if "train" is the object of "were watching," then something else has to serve as the subject of "was passing." Such is the structure and logic which our brains use to process the language. Most students need little help in learning to identify verbs. Many students may say that they have difficulty. That is because they have not been expected to learn to do so. (Instead, they have been expected to memorize the definition.) Giving students the definition is fine, but don't test them on the definition: test them on their ability to use it. (See Chapter Seven for more on teaching methods.) Every year I have a few students who begin by telling me that "is" is a preposition and that "of" is a verb, but even these students soon straighten themselves out. A more important difficulty is helping them distinguish finite verbs from verbals. I usually give them a single example: Students can see that in (a) "was planting" functions as the verb in the sentence pattern, that in (b) it functions as a noun, the subject of the sentence, and that in (c), as an adjective, modifying "he." These examples give them a sense of the range of a verbís functions, but they still need to be able to exclude the verbals. They can do so by relying on their unconscious knowledge of English. Most students can easily identify the subjects and finite verbs in our examples, and, if they are in doubt, they can try to use the verb in a short sentence of their own. For example, in the sentencea.) He was planting a garden. I have already suggested that English has four variations of one basic sentence pattern. Attempts to teach grammar through five, ten, or twenty sentence patterns only confuse students, first by undercutting the basic simplicity of syntax, and second by suggesting that there is something special about the five, ten, or twenty patterns the author has chosen to demonstrate. There is something special about the four variations since they reflect the presence and nature of the complement. Once again the traditional approach has been backward, deductive rather than inductive. Students have been given definitions for transitive, intransitive, and linking verbs. They have been asked to memorize lists of linking verbs. Implied in this process is the belief that the student should recognize the nature of the verb first, and from it determine the sentence pattern. If this process is reversed, if the student starts from the pattern, s/he need not learn the distinctions among transitive, intransitive and linking verbs. The four variations can be distinguished simply by making a question with the verb in the pattern (Verb +"whom" or "what"?). The answer to the question will determine both the pattern and, for those who are interested, whether the verb is transitive, etc. Subject/Verb. If nothing answers the question "Verb + whom or what?", the pattern is S/V. (The verb is intransitive.) Subject/Verb/Predicate Adjective. If the word that answers the question "what?" after the verb is an adjective, the pattern is S/V/PA. (The verb is a linking verb.) Subject/Verb/Predicate Noun. If the word that answers the question is a noun that renames the subject and the verb implies an equality or identity between subject and complement, the pattern is S/V/PN. (The verb is a linking verb.) Ed remained a child. ("Remained" here means "was" and "continues to

be.")

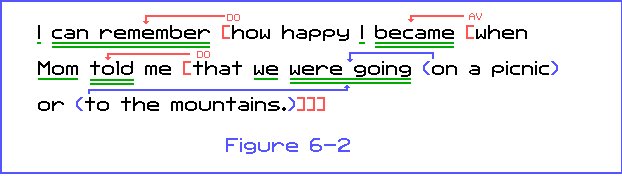

A sentence such as "Sleeping children resemble angels." implies that when they are sleeping, children equal angels, at least in appearance. "Angels" is therefore a predicate noun. Note that the criteria of implied equality between subject and complement eliminates "herself" from consideration as a predicate noun is a sentence such as "She washes herself." "Washes" does not imply equality. Subject/Verb/(Indirect Object) Direct Object. If a word or construction answers the question "whom or what?" after a verb and is not a predicate noun or predicate adjective, it has to be an indirect or direct object. (The principle of exclusion is here combined with the principle of comprehensiveness: all verbs fall into one of four patterns, if a verb is not in pattern a, b, or c, then it must, by exclusion, be in d.) An indirect object indicates the person "for" or "to" whom something is done. (The verb is transitive.) These four definitions of sentence variations are not only simpler and easier to use than the traditional approach that focuses on the nature of the verb, they also concentrate studentsí attention on the meaning of the sentence. Some superficial exceptions, and a real one Simple words often pose the biggest problems. Consider: Many texts include (a) as an additional pattern -- the "there is/are" pattern. Semantically and syntactically, it is true that the "there is/are" pattern creates all sorts of problems -- for the linguist. Students, however, rarely misuse the pattern and there is no reason to make a big deal about it. It can, from their point of view, simply be treated as the S/V/PN pattern. (For more about this, see the discussion of nouns used as adverbs, below.) The relationship of (b) to (a) is obvious, but it requires additional explanation. Students have no trouble seeing it as a doubled pattern, i.e, a S/V pattern ("The principal goes.") superimposed on the S/V/PN pattern ("There is the principal.") Since "to be" is understood, the verb that appears in the sentence will always be the one from the S/V pattern. Both (c) and (d) are explicable through ellipsis: "Jane is *located* here," or "Jane is *present* here."; "The game was *played on* Tuesday." Examples (a) through (d) thus pose superficial exceptions since they can be explained with the four patterns.a.) There are five men here. Example (e) demonstrates a special characteristic of the S/V/PN pattern. Almost any word or construction can be emphasized by taking it out of its sentence, preceding it with an "It is" and then following it with the rest of the sentence preceded by a "that" or "who": Sarah hurt her knee here.Even though "here" is usually an adverb and "hurt" is usually a verb, in this pattern they function as predicate nouns. This "it is/was" variation, a real exception, is related to the delayed subject. I introduce it at this point because it is met with more frequently than the delayed subject. SUBORDINATE CLAUSES A clause is a subject/finite verb pattern plus all the words that go to it. Much nonsense has been written about subordinate and main clauses. Thus, there is the definition of a main clause as "a clause that can stand alone." Teachers who use that definition have not thought very much about what they are doing. "He is a coward" can stand alone, but in "Bill thinks he is a coward," it is a subordinate clause. Some teachers argue that there is an ellipsed "that" in front of the "he" when it is a subordinate clause, but once again they are arguing backwards. They know when to put the ellipsed "that" in only because they know that it is a subordinate clause. Students who cannot distinguish main from subordinate clauses have no way of telling when there is or when there is not an ellipsed "that." The only practical definition of subordinate clauses is that they function as nouns, adjectives or adverbs in relation to another word or construction. Main clauses have no such function: their pattern is the pattern to which everything else in the sentence relates. Students who have been underlining all the subjects and finite verbs in sentences will have little trouble with clauses -- there is one clause for every subject/verb pattern. In analyzing clause structure, students find it easiest to work backwards, starting with the last S/V in the sentence: I can remember how happy I became when Mom told me that we were going on a picnic or to the mountains.The last subject/verb is "we were going." The student next has to decide where the clause begins and ends, i.e. which words "go to" this subject and verb. Introducing students to subordinate conjunctions will now help them find the beginnings of subordinate clauses more quickly and accurately. Having determined the boundaries of the clause, the studentís final job is to determine which word, outside the clause, the clause may "go to." I encourage students to look for a clause's function in a specific order: check for noun functions first, then adjectival, finally adverbial. Some students, if they do not follow this order, tend to miss noun functions. In our example, the "that we were going on a picnic or to the mountains" clause functions as the direct object of "told." It is therefore a noun clause. "Told" is the verb in the "when ... mountains" clause, which functions as an adverb to "became," the verb in the S/V/PN pattern (I / became / happy). This pattern is the core of the "how ... mountains" clause that functions as the direct object of "can remember." Since every sentence has to have at least one main clause, i.e., one main S/V pattern, and since "can remember" is the only pattern left, it has to be the main subject and verb. Since a clause is defined as a S/V/complement pattern and all the words or constructions that go to it, the main clause is the entire sentence. The analyzed sentence is shown in Figure 6-2. Students are usually amazed to find clauses within clauses, brackets within brackets. But so the language works.

Clauses and Ellipsis Ellipsis can assist students with such perennial problems as the comparative constructions. An apparently innocent, Freshman coed wrote: Someone could have trained her [a horse] better than me.As with most errors, there is logic behind it. The "than me" probably derives from analogy with prepositional phrases, and such phrases take the objective case. We can, however, help students see the problem by showing them how to restore the "than me" to its clausal form: Someone could have trained her better than I *could have*."Frequently the ellipsed words have already appeared in the sentence: She is as quick as he *is quick*.But consider: He arrived before the sun.Although it could be argued that this means that "he arrived before the sun arrived," the argument would be weak. If the sun arrived in the sense that he did, their resulting proximity would have burned both him and the writer. Clearly the ellipsed word is "rose": "He arrived before the sun *rose*." "Rose" is, however, implied by "arrived." If the writer meant "He arrived before the sun set," he would have had to have supplied the word "set." (Note too how this example illustrates the close relationship between clauses and prepositional phrases.) The exact degree and form of ellipsis can be surprising: Using a promise (of an ice cream cone) [when he awakens], I convince the munchkin [that a nap would be nice.]The "that ... nice" clause functions as the direct object of the main verb "convince." But how does the "when he awakens" function? It is clearly an adverbial clause, since it doesnít tell us anything about the "ice cream cone"; it tells us when he will get it. The clause does not modify "using," since the promise will not be used when he awakens, but before he goes to sleep. What, then, does the clause modify? It modifies an ellipsed verb in an almost totally ellipsed clause: Using a promise (of [*I will give him* an ice cream cone [when he awakens]]), I convince the munchkin [that a nap would be nice.]"When he awakens" modifies "will give" in the noun clause "*I ...* ... awakens," which functions as the object of the preposition "of." Ellipsis also explains the SEMI-REDUCED clause: Although not wealthy, they were not poor.This construction, neither common nor rare, occurs most often with subordinate conjunctions that cannot serve as prepositions. With words that can serve both functions, the construction can be interpreted as a prepositional phrase with a gerund as its object: "After swimming, they felt hungry." VERBALS In "Thinking Visually about Writing," Charles Suhor, a prominent member of NCTE, places grammar in his "Content Area Model" and ridicules it regularly. Not satisfied with references to research and a studentsí (collective) poem against grammar, he decides to bring Piaget into the attack: In terms of Piagetian theory and research, most students do not have sufficient skill in manipulating abstractions to understand, digest, and apply dense concepts like the absolute phrase, the gerund, and the participle. (78-79)His statement forces one to wonder how well he has assimilated Piagetís theory. (Piaget, to my knowledge, never states that students should not study grammar, and Vygotsky, whose name is often linked with Piagetís, specifically argues that they should. (Thought 100) Since Professor Suhor has been talking about high school students, we must assume that he is telling us that 10th, 11th, and 12th grade students cannot handle concepts such as the gerund -- that they donít have the ability to manipulate such abstractions. But are these not the same students who somehow manage to manipulate geometry, algebra, trigonometry, and even, in many cases, calculus? Had Professor Suhor thought about it, he might have decided that the concept of "gerund" is no more "dense" than an axiom in geometry. His problem, quite simply, is that he considers only the students, not their prior preparation. If students cannot identify all the finite verbs in a passage -- and given current instruction, they cannot -- then they will have tremendous problems with verbals. In Piagetian terms, if they have not conquered the plateau of finite verbs, they have no hope of ascending to verbals. But if they have, if they can identify all the prepositional phrases and all the subordinate clauses (hence, all the finite verbs) in a passage, they are ready to study verbals. Any verb in a sentence that does not function as a finite verb has to be one of the three verbals: Gerunds always function as nouns. Gerundives always function as adjectives.Most textbooks refer to gerundives as "participles," but to do so is confusing. "Participle" designates the form of the word -- the "-ing," "-ed," "-en," etc. ending. Both gerunds and gerundives have participial form. Infinitives do not. Students can thus distinguish gerunds and gerundives from infinitives by their form. Then they can distinguish gerunds from gerundives by their function. The easiest way to identify infinitives is by the principle of exclusion: if a verb is not finite, not a gerund, and not a gerundive, then it has to be an infinitive. There is no other choice left. (The "to" with many infinitives helps students, but not all infinitives include the "to.") The similarity of verbals to finite verbs is often overlooked in pedagogical grammars. Verbals are condensed, or reduced versions of the basic sentence pattern. Like finite verbs, they have subjects and complements. Subjects of Verbals The subject of a gerund is expressed as a possessive noun: "The cricketsí chirping kept me awake." If the gerund denotes a general action, performable by anyone, the subject is usually ellipsed: "*Anyoneís* swimming is good exercise." This expanded sentence sounds strange, and indeed it is: we have become accustomed to ellipsis. But when the subject of a gerund is ellipsed, it is always there, understood. Note, for example, that no one would interpret "worms" as the subject of the sentence, but who would not accept deer or dogs? The subject of a gerundive is the noun or pronoun it modifies. It is that simple. The subject of an infinitive, if expressed, is in the objective case. This question of case is meaningful only in relation to pronouns (Let us go), since nouns in English no longer show a distinction in case. Frequently, the subject of an infinitive is simply understood -- in "Bill wanted to see the museum" it is clear that Bill wanted Bill to see the museum, otherwise the subject of the infinitive would have been supplied. There is a slim chance that students will run into a minor problem in a sentence such as: For Bill to go to New York is a bad idea.Infinitives that have subjects apparently canít simply function as subjects: they require the preposition "for." My way of explaining this construction is to say that the infinitive is the object of the preposition and that the prepositional phrase functions as a noun, the subject of the sentence. By the time they get to infinitives, students donít have much, if any problem with this since they have already detected the pedagogical lie about "all" prepositional phrases functioning as adjectives or adverbs: they have seen a few as indirect objects. (It is very important not to get hung up on this explanation. Linguists won't like it, but students accept it, the construction is rare, students never make a mistake with it, and they have more important grammatical things to learn.) Complements of Verbals Logically, complements of verbals would seem

to need little discussion, but I have found that people well-trained in

traditional grammar are often surprised to realize that verbals can have

complements just as finite verbs have and that these complements can be

found and distinguished in the same way that one finds and distinguishes

the complements of finite verbs, i.e., by making a question with "what

or whom" after the verbal. Their surprise is another indication of the

categorizing, rather than conceptualizing approach usually taken toward

traditional syntax. Instead of looking for similarities, traditional grammarians

have stressed differences. Note that the conceptual approach not only simplifies,

it also suggests the relative importance of concepts: the subject/verb/optional

complement pattern is basic not only to every main and subordinate clause,

but also to every verbal. It is truly the fundamental pattern of the language!

NOTING PROGRESS WITH SYNTACTIC CONNECTIONS In discussing prepositional phrases, I noted

that the student who can identify such phrases and the words which they

modify can already understand about 40% of the syntactic connections in

the average piece of writing. We have since added subject/verb patterns,

subordinate clauses, and verbals. If we add regular adjectives and adverbs,

which I do not "teach" at the college level, but which students assimilate

on their own, I can safely say that students can now explain between 97

and 99% of the connections in any passage. (The 99% is for their own writing;

the 97%, for the more complex writing of professionals.) I cannot "prove"

this, but anyone can prove it for himself. If I were to illustrate my claim

by analyzing a hundred fifty word sentences, skeptics could always claim

that I intentionally selected sentences to avoid problems. More sentences

will be analyzed in the following discussion of the remaining constructions,

but the point I wish to make it this: if my claim is valid, then the way

that students find these other constructions is through the principle of

exclusion. Having analyzed 97 or 99% of the connections in a sentence (or

paragraph), students easily see the words that they canít yet explain.

These words are all that they have to worry about as they attend to the

following constructions.

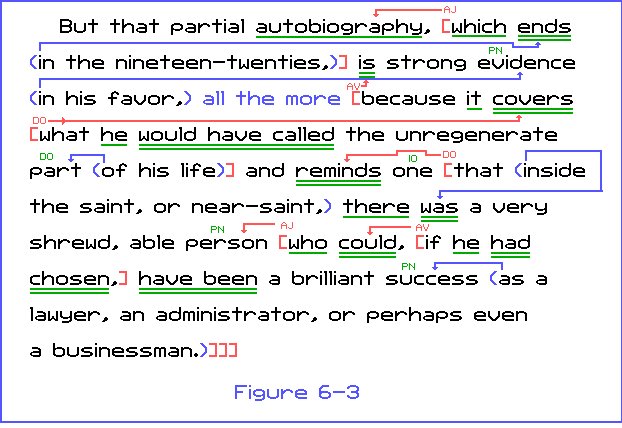

OTHER CONSTRUCTIONS Nouns Used as Adverbs Some nouns function as adverbs, usually to indicate a spatial or temporal orientation: "The plane crashed five miles from here." The construction is close to the prepositional phrase: but, as in our example, there frequently is no preposition that fits such that we could say that it is ellipsed. Thus the construction needs to be included in the theory. And it proves useful. As we noted in the previous chapter, it provides a simple explanation for "fishing" in:They drove six miles. Another interesting noun used as an adverb appears in this sentence from George Orwellís "Reflections on Gandhi": But this partial autobiography, which ends in the nineteen-twenties, is strong evidence in his favor, all the more because it covers what he would have called the unregenerate part of his life and reminds one that inside the saint, or near-saint, there was a very shrewd, able person who could, if he had chosen, have been a brilliant success as a lawyer, an administrator, or perhaps even a businessman.This sixty-nine word main clause is complex, but readily analyzable with the concepts we have discussed. If we mark and label the prepositional phrases and clauses, we get the results shown in Figure 6-3.

Only one connection in this sentence raises a major question: how does "all the more" fit? The adjectives "all" and "the" obviously connect with "more," thereby indicating that "more" is a noun. How does "all the more" function? As an adverb, modifying the "because" clause. Additional proof is that we could substitute "especially" for "all the more." (Note, in passing, the fourth level embedding of the "if he had chosen" clause.) Orwellís sentence allows me to repeat an important

point -- the theory presented in this book does not provide "ultimate"

explanations; it provides explanations that satisfy, in some cases more

than satisfy, the average student. The better student may wish to explore

syntax beyond this theory. Most linguists, for example, would not be satisfied

by my explanation of "all the more." And what is "perhaps"? Is it an adverb?

Or an interjection? Is "even" here an adjective, or an adverb? Such questions

can be pursued endlessly, if one is interested in them. But note that they

are all a question of "which explanation is better," not of "is there an

explanation." Pedagogically, our principle of "alternative explanations"

allows us to accept both, or more, if there are more. If students in my

courses are interested in such questions, we discuss them; if they seem

satisfied with what they have, we move on.

Appositives Most definitions of "appositive" limit the concept to nouns, i.e., two nouns joined by their referring to the same thing with no preposition or conjunction joining them. Practical analysis will quickly reveal that other parts of speech can also function as appositives: She struggled, kicked and bit, until her attacker let her go.The three finite verbs do not denote three distinct acts: "struggled" denotes a general concept which is made more specific in "kicked" and "bit." Can we not then say that the last two finite verbs function in apposition? Another sentence from Orwellís essay illustrates how constructions, in this case, prepositional phrases, can also function appositionally: In Gandhiís case the questions one feels inclined to ask are: to what extent was Gandhi moved by vanity -- by the consciousness of himself as a humble, naked old man, sitting on a praying mat and shaking empires by sheer spiritual power -- and to what extent did he compromise his own principles by entering politics, which of their nature are inseparable from coercion and fraud?Is there a better, simpler way of explaining "by the consciousness" and the phrases dependent on it than to say that the phrase is an appositive to "by vanity"? The concept of the appositive grows still more once we realize that not all appositives have to be composed of identical parts of speech, i.e., noun and noun, verb and verb. etc. The following sentence was written by a mother who had returned to college: Heavy feet followed me on up the attic stairs -- treasure-filled attic, hiding place for Motherís Day cards, carefully printed on pasty colored paper, yellowed packets of letters, saved since World War II.The identity here is not of meaning, but of the word itself: the adjective "attic" turns into the noun. But is there an easier way of explaining this than as an appositive? In the following sentence, also written by a student, the apposition is between an infinitive phrase and a noun: Left alone, and needled by that nagging sense of guilt, she busies herself cleaning house and lets the "coffee pot boil over," an effective image to describe her anger, which is short lived, as night softens her memory of the harsh morning light and she falls prey to her lust again.

Direct address is similar to an interjection

except that it indicates the intended audience, rather than a speakerís

comment: "Mary, Jane called."

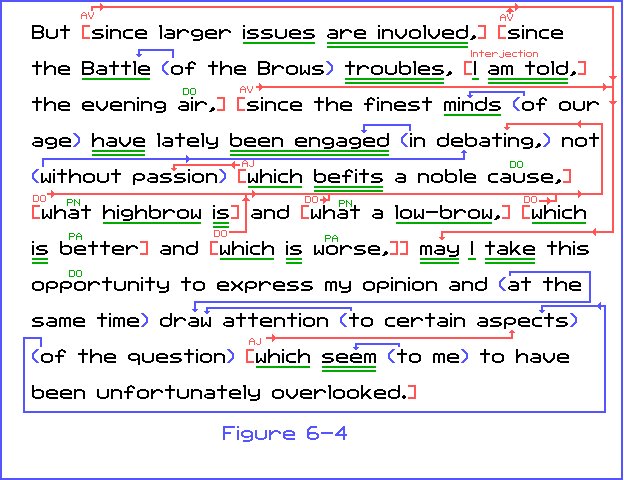

Noun Absolutes Most texts define the noun absolute as a noun plus gerundive construction that usually functions as an adverb but may appear as a noun: Supper having been finished, the family went to the ballgame.What these texts leave out is that the gerundive is often ellipsed: Hands *being* behind his back, Dad watched as Fred rode his bike down the street.Interestingly, punctuation can make the difference between a compound sentence and a noun absolute): a.) The plane stood upright; its tail pointed back at the sky.The semicolon, a signal of a full stop, makes "pointed" in (a) an active, finite verb. But the comma in (b) allows us to read "pointed" as a passive participle ("*having been* pointed"), thereby changing the construction into a noun absolute. A similar phenomenon occurs in the following sentence, written by a student: The car was smashed. It lay sideways in the road like a dying dragon, its hood reared skyward, a pool of shimmering glass scales around it, weak puffs of smoke rising from its broken front grille into the crisp night air.At the risk of being repetitious, perhaps I should describe how students go about identifying these noun absolutes. This example is interesting because it is particularly difficult. By the time they get to noun absolutes, students have been analyzing prepositional phrases, clauses, and even verbals for some time. When they first meet this sentence, therefore, their first task is to analyze everything they can. Some students will want to underline "reared" as a finite, active verb, but if they do so, they then must note that it is preceded by a comma-splice. Even if they do this, they are still left with three unanalyzed words: "pool," "puffs," and "rising." Their task is to shift through their list of "other constructions" to see if they can use them to explain these words. "Puffs ... rising" is then fairly easily identified as a noun absolute. If they are intelligent, and a good number of them are, they also see that "hood reared" is one likewise. This leaves "pool." How can they explain this noun construction sitting between two noun absolutes? If they use their brain, the pattern is simple: itís a noun absolute: "a pool of shimmering glass scales *being* around it." Most students do not need to be able to make this analysis. The student who wrote the sentence, for example, has an excellent command of syntax -- and a vivid imagination, and most students who use these "other constructions" make few errors with them. (See Chapter Eight on syntactic errors.) I would argue, however, that every teacher of English from seventh grade onward should be able to make the explanation; otherwise he might mark the sentence as a comma-splice. As a general rule, the noun in a noun absolute comes first, but in some cases, especially with clauses, the gerundive does: Given [that heís willing to play,] will the referees let him?Some teachers will mark this as a dangling modifier, but I canít see why it should be so considered. Does it not mean: [That heís willing to play] *having been* given, ... ?or, in other words, is it not simply a noun plus gerundive construction? As adverbs, noun absolutes appear rarely. My research, indicates that Edmund Wilson uses one for every fifty main clauses, E.B. White uses one for every hundred, and Max Beerbohm, E.M Forster, and James Baldwin use less than one in every fifty. But if we turn to their use as nouns, they are more common. Their noun function is obscured, however, because the words can usually be explained in another way. The following sentence is from Max Beerbohmís "The Top Hat": He wears a top hat in that fine portrait of him sitting in his garden, immensely corpulent, but still full of energy and animation, of benignity and genius.Students can, of course, explain "him" as the object of the preposition "of" and "sitting" as a gerundive modifying it, but such an explanation, although allowable, deflates the nexal connection of "him" and "sitting," a connection that can be seen if we rephrase it to be "portrait in which he is sitting." "Him" and "sitting," in other words, go together first, and then the noun absolute becomes the object of the preposition. I must admit that it was a student who first made me pay attention to the noun function of noun absolutes. The class was discussing the sentence: They watched the windmill spinning against the sky.Someone had already analyzed "windmill" as the direct object of "watched" and "spinning" as a gerundive modifying it, but one student wasnít satisfied. The sentence, she insisted, doesnít really mean "We watched the windmill": it means we watched the "windmill spinning": the noun absolute functions as the direct object. Having read Jespersen on nexus, I wasnít about to tell her that she was wrong. She wasnít. Note also how close the construction is to the gerund plus subject -- "windmillís spinning." The noun absolute allows us to see the connection between "windmill" and "spinning" as primary, and then to take the entire construction as the direct object of "watched." Delayed, or Postponed Subjects The traditional focus on individual words has almost totally obscured what I call the "delayed subject." I took the liberty of naming it because I couldnít find it in the grammar books. Having named it and prepared materials about it for my students, I found it in Christensen: he calls it a "postponed subject." It is a modification of the basic sentence pattern in which the subject position is filled by an anticipatory "it" and the true, delayed subject appears later in the sentence: It is easy to fall in love.Although the construction usually appears with a noun clause or infinitive, other constructions or even nouns themselves may act as delayed subjects: Gerund: It is difficult, waiting for your wife to have a baby. Noun Absolute: It was foolish, people of their age trying to climb a mountain. Noun: It was fortunate, the trip he took. In delayed subjects, the idea to which the pronoun, usually "it" but not necessarily, refers comes after the pronoun. If that idea is not supplied, the pronoun remains meaningless. As with all the constructions, delayed subjects can be embedded in other subordinate constructions. The following sentence was written by a seventh grade student: The old man thought it funny that the trees, now strong and stable as he once was, still grew and became mightier, while he grew weaker and less sure-footed, swaying in the wind.The sentence is remarkable for the level of its embeddings, and especially for the reduction of "*which were* now strong and stable" to the simpler "now strong and stable." Everything after the "that" is easily analyzed in terms of clauses and the single gerundive "swaying," but what is the function of the "that" clause? It is a delayed subject to "it" in the infinitive construction "it *to be* funny," "funny" thus functioning as a predicate adjective after the ellipsed infinitive, and the infinitive, with, of course, everything that "goes to" it, functioning as the direct object of "thought." (I explain the ellipsed word as the infinitive "to be" by analogy with the "They made him captain" construction. A student could justifiably say that the ellipsed word is "was.") Retained Complements Retained complements are simply predicate nouns, predicate adjectives, or direct or indirect objects that appear after passive verbs, whether finite or verbals: Most textbooks limit this construction to retained objects and objective complements. But expanding the concept to include predicate nouns and predicate adjectives simplifies explanations: a.) Murray was considered foolish.These two examples are identical except that the first ends with a retained predicate adjective, the second with a retained predicate noun. If we exclude the concept of retained predicate adjectives and nouns, then (a) requires the following explanation: "Murray was considered foolish" is the passive form of the active: "Someone considered Murray foolish." "Murray" is the subject, and "foolish" is the predicate adjective of the ellipsed infinitive "to be," which functions as the direct object of "considered." In the passive version, the ellipsed infinitive is the retained object and "foolish" is a predicate adjective after it.Rather than force students to go through this cumbersome technical explanation, I simply accept "retained predicate adjective" or "retained predicate noun." Interjections That constructions function as interjections has already been suggested: "In fact" here simply emphasizes the writerís belief that the sentence is factual, whereas "in my opinion" suggests that the sentence may not be. Some transformational grammarians consider them as "sentence modifiers," which is a poor pedagogical term since it blurs the distinction between their distinctly a-syntactic, meta-discourse nature, and other "modifiers."In fact, everyone came. The only construction that probably should not be used as an interjection is the gerundive, since in a sentence such as Telling the truth, the fish was only six inches long, "telling" will be interpreted as modifying "fish." "To tell the truth" would make an interjection. When clauses are used as interjections, they are usually set off either by dashes or parentheses: That island -- wherever it is -- is a tropical paradise.But note: He wrote, I suppose, to ask for money.Here the "I suppose" can be considered as the main S/V with the "he wrote" clause as its direct object, or, by the principle of alternative explanations, as an interjection. ***** I anticipate that some of my readers will not believe that I have covered all of the constructions needed to explain how any word in any sentence is related to the basic pattern. We are much too accustomed to being inundated with tremendous lists of exceptions and to being told that grammar is complicated. Grammar does include numerous exceptions to rules, but almost all of these exceptions are in the area of usage, not of syntax. Syntax is complicated, not as a result of numerous constructions, but as a result of complicated combinations of constructions. We embed clauses within clauses, and these clauses within verbals or prepositional phrases. Untangling these combinations is not always easy -- that is why I have suggested a sequential approach to analysis. Although attempting to "prove" the comprehensiveness of the theory by analyzing sentences is open to the charge that the sentences have been selected to avoid problems, letís look at one more sentence, an 87-word main clause from Virginia Woolfís "Middlebrow": But since larger issues are involved, since the Battle of the Brows troubles, I am told, the evening air, since the finest minds of our age have lately been engaged in debating, not without that passion which befits a noble cause, what a highbrow is and what a lowbrow, which is better and which is worse, may I take this opportunity to express my opinion and at the same time draw attention to certain aspects of the question which seem to me to have been unfortunately overlooked.Figure 6-4 shows the analyzed sentence.

The initial "But," which relates this sentence to a preceding one, is followed by three "since" clauses, all functioning adverbially to "may take." The pattern in the first of these clauses can be described as either S/V (issues / are involved), or as S/V/PA (issues / are / involved). The second clause requires little further explanation except for the embedded "I am told," which I prefer to explain as an interjection. In it Woolf distances herself from the content of the statement, says, in effect, I do not take responsibility for this idea -- others have told it to me. The construction could, of course, be analyzed in another way, as "since I am told *that* the Battle of the Brows troubles the evening air." This explanation makes the "that" clause a retained direct object of "told." The third "since" clause is more complicated, but once again it is because of the number of embedded constructions, not their complexity: since the finest minds of our age have lately been engaged in debating, not without that passion which befits a noble cause, what a highbrow is and what a lowbrow, which is better and which is worse,"Which befits a noble cause" is a simple S/V/DO adjectival clause to "passion," which is the object of "without." The prepositional phrase functions as an adverb to "debating" and is modified by the adverb "not." "Debating," the object of "in" in the prepositional phrase which functions as an adverb to "have been engaged," has four clauses as its objects. The verb in the second of these clauses ("what a lowbrow") has been ellipsed. In the first two of these clauses, the pronoun "what" serves as the predicate noun within the clause pattern. Two infinitives modify the main finite verb ("may take") in the sentence: may I take this opportunity to express my opinion and at the same time draw attention to certain aspects of the question which seem to me to have been unfortunately overlooked."Opinion" is the direct object of "to express," and "at the same time" modifies "draw." "Attention" is the direct object of "draw." "Of the question" modifies "aspects," and "to certain aspects" modifies "draw." The final clause, "which ... overlooked," functions as an adjective to "aspects." The verb construction in this clause can be explained in several ways. Some people prefer to see it as a single passive verb: Some teachers will balk at the preceding analysis, particularly at some of the alternative explanations. But as I noted in Chapter Three, as teachers, we cannot impose an interpretation on students. When we try to, students balk and stop paying attention. Each of the alternatives is justifiable within the "rules" of the theory. Pedagogically, it is very important that teachers not make a fuss about such explanations -- students have no trouble using a verb such as "seem to have been overlooked." Teachers who devote a great deal of time to explaining and arguing such constructions are taking time away from what the students really need -- the larger pattern of how constructions are embedded in constructions. Some linguists, influenced by generative grammar, will have a different objection to this theory -- they will complain that it does not go far enough, that it does not explain how the surface structures are generated from the deep structure. Such linguists fail to realize that students have no need for such generative explanations. (As we noted in an earlier chapter, Chomsky himself suggested that students should study not transformational grammar, but a grammar such as Jespersenís.) Students do not need to look at a sentence and explain how a mind created the connections among words and constructions; they need to be able to look at it and see what those connections are: they need to be able to see that a noun clause is connected to a verb as its direct object, etc. For studentsí purposes, the preceding theory is totally adequate, even for courses in advanced stylistics in graduate school. The theory requires that the analyst, be it student or teacher, think. Some constructions may be beyond the ability of any student to explain, and the teacher may have to bring to bear all of her knowledge of the language. Hunt, for example, discusses: In eight years of working with this theory, I have found only one sentence which I cannot explain to my own satisfaction: If it had not been for his daughter, the hotel would certainly have gone bankrupt long before. (James Baldwin)Students seem satisfied with the explanation of "for his daughter" as a prepositional phrase modifying "had been," but this explanation relegates "daughter" to a subordinate construction. Perhaps it is the linguist in me, but I feel that "daughter" needs a better explanation. The teacher in me, however, refuses to let the linguist force such "problems" onto my students. Students first need to understand the basic theory, to be able to analyze the mass of sentence structure. This theory helps them do so.

1. Although most of the theory presented in this chapter is based on traditional concepts, some of the explanations are different from what you will find in traditional, structural, transformational, and/or other grammar textbooks. What reasons might you have for accepting (or rejecting) the explanations given here? 2. Select a paragraph from a student's essay and see if you can analyze it by using the constructions described in this chapter. How much of the paragraph could you analyze? How much do you think you could teach students to analyze? 3. Which explanations of constructions and/or method did you find confusing?

How well can you explain what you read to someone who did not read this

chapter?

|

||||||

|

This border is based on Madonna & Child (The Small Cowper Madonna), 1505 National Gallery of Art at Washington D.C. Carol Gerten's Fine Art http://sunsite.sut.ac.jp/cjackson/index.html Click here for the

directory of my backgrounds based on art.

|