Research on Natural Syntactic Development

Volumes of research have been published on natural syntactic development, but most of it, especially that of the last twenty years, is irrelevant to what goes on in our schools. David Crystal, for example, summarizes a famous experiment by Carol Chomsky in which she examines children’s ability to distinguish the meanings of "hard to see" and "easy to see": What Carol Chomsky did was to present a group of children, aged from five upwards, with a blindfolded doll, and ask them "Is this doll easy to see or hard to see?" If the children said "Easy to see" then it is argued that they have learned the distinction; but if they said "Hard to see," and amplified their comment (upon request) by for instance, "Because it’s got a blindfold on," then it is argued that they had not learned it. The Chomsky results showed that before the age of six this distinction was hardly ever learned, whereas after seven it was known to nearly all children in the sample. (Child 49)The statement that such research is "pedagogically irrelevant" requires amplification. As Crystal quite correctly goes on to note: "it is possible to extract a general conclusion from this and similar experiments, namely, that there are matters of structural (and in this case also semantic) interpretation which it takes children many years to acquire." But once we accept the idea that syntactic development occurs over a period of years, perhaps even throughout an individual’s whole life, no further pedagogical conclusions can be drawn from such research: it suggests nothing about what we could or should teach. At age five, most children have trouble with this particular distinction; at age eight, most of them have mastered it. But they have figured it out for themselves -- no "instruction" was involved, no "pedagogy." The number of complex structures which children somehow figure out for themselves is awesome. I remember, for example, listening to my four-year-old son, speaking about a light, and saying, "Turn on it," instead of "Turn it on." Why children go through this stage, and how they work themselves through it, again pose complicated linguistic and developmental questions. But these questions are not "pedagogical": children work their way out of them, all on their own, without any other instruction than access to conversations, just as they work their way through and out of "I readed a book" and "I cutted up the paper." There are many things we can’t teach, and shouldn’t try to. This does not mean that the developmental research of the last two decades is totally valueless: it has provided and confirmed some important general principles of language development, and, in such fields as teaching the learning disabled, it even provides many practical suggestions. But for the normal child, studies which involve linguistic development in pre-school children are irrelevant. For relevant studies, we must return to the sixties and seventies and the work of such people as Kellogg Hunt, Roy O’Donnell and Walter Loban. Hunt's "T-Unit" The work of these researchers centered on the child’s syntactic development between the ages of five and eighteen. The sentences of adults are obviously different than the sentences of children, and researchers had been looking for some way to measure the differences. A simple measure of words per sentence does not work because third, fourth, and some fifth graders create long sentences by compounding main clauses with "and." Hunt wondered if a count per main clause (defined as including all subordinate clauses) would be a better measure. Because the grammarians cannot agree about their terms (See Chapter One.), Hunt used the term "T-unit" -- for "minimal terminable unit." (In doing so, of course, he simply added to the terminological chaos.) To denote what he was measuring, he used the term "maturity," but he was careful to define it: In this study the word "maturity" is intended to designate nothing more than "the observed characteristics of writers in an older grade." It has nothing to do with whether older students write "better" in any general stylistic sense. [Grammatical Structures Written at Three Grade Levels. 1965. NCTE Research Report #3, p. 5]Hunt convincingly demonstrated the validity of the T-unit as the "basic" unit of measurement. I emphasize "basic" because Hunt himself notes, as we will see, that it is not the only gauge. All of the subsequent major research studies have used Hunt's "T-unit" as their fundamental yardstick (although, as noted in the previous chapter, some researchers changed it from 36" to 30".) Simply stated, Hunt counted the number of words per main clause in the writing of students in different grades and found that the average number increased steadily from grade to grade. Hunt’s study was corroborated by O’Donnell, to give the following figures, as summarized by O'Hare (22):

The figure for "Adults" is from Hunt’s study of essays published in

The

Atlantic and Harper’s. Although there are numerous questions

surrounding such statistical studies, the basic conclusion remains valid:

if samples of writing are taken from students (of similar socio-economic

status) at different grade levels, the average number of words per main

clause will show an increase similar to that above. Likewise, a study of

passages from a variety of published writers will often result in a count

of approximately twenty words per main clause.

The Natural Development of Subordinate Clauses Hunt, O'Donnell, and Loban all concluded that subordinate clauses "blossom" (to use Hunt's term) between seventh and eighth grades. The following table is based on O'Hare's summary (p. 22) of Hunt's and O'Donnell's studies.

We need to be cautious with these results. The numbers for fourth, eighth,

twelfth, and "Superior Adults" come from Hunt's study; the others, from

O'Donnell's. Differences in the way constructions were defined and counted

may make the results not totally comparable. The table, however, does suggest

a major "blossoming" of subordinate clauses between seventh and eighth

grades. We also need to remember that neither Hunt nor O'Donnell was doing

comparative ("horse-race") studies. They simply collected and analyzed

samples of students' writing at different grade levels, and they rarely,

if ever, discussed the instruction (in grammar or writing) that the students

had received.

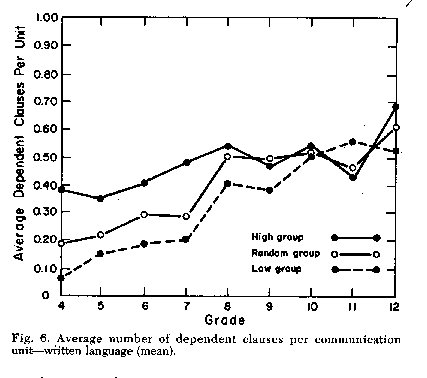

One of the most enigmatic features in the whole array of data collected in this study is the showing that kindergarten children used relative clauses more frequently than did children at any other stage, in either speech or writing. Harrell (1957), studying the language of children from 9 to 15 years of age, found that such clauses were used less frequently than noun clauses or adverb clauses in oral stories produced at each age level, and less frequently, too, in the written stories of 9-year-olds and 11-year-olds. Noting that Watts (1944) had made a similar observation about the writing of children up to the age of 11, [i.e. sixth grade, EV] Harrell inferred that younger children have a less well developed understanding of the uses of adjectives clauses than of other types and that they find them harder to manipulate. (60-61)I have quoted this at length because it further supports the "that" knowledge developed by these researchers, and it also suggests their reticence to discuss "why." O'Donnell himself simply presents it as "enigmatic," and Harrell apparently suggested that adjective clauses are more difficult to manipulate without exploring why. Perhaps the most interesting study here, however, is Loban's. As its title suggests (Language Development: Kindergarten through Grade Twelve), Loban's study is the most comprehensive. In addition to its time span, Loban, like O'Donnell, studied both oral and written language. But he also divided the students whose sentences he studied into three groups, high, low, and random. The following graph (from page 39), clearly reflects the sharp increase in subordinate clauses between seventh and eighth grade for the low and random groups. Note that the "high" group shows a much slower increase during this grade level, and that, between eighth and ninth grades, all three groups show a decrease, the decrease being most significant for the high group. (I'll have more to say about this later.)

All of the researchers attempted to break "subordinate clauses" into

smaller categories (noun clauses, adjective, adverbial, etc.), but years

of attempting this type of research have convinced me that such distinctions

become very tenuous unless the transcripts of the original data are available

for review.

O'Donnell and the Concept of "Formulas" I suggested above that the researchers

whose work we are considering were focused on the "what" of natural syntactic

development. Probably with good reason, they were very hesitant to explore

the "why." One can't very well explain why things happen within a dynamic

system until one has at least a fairly good picture of what its components

are. The "why" question must have perplexed these researchers, but in a

subject area as new and complex as this, they had to focus on one thing

at a time. In publishing their work, moreover, their primary objective

was to get their main ideas accepted. Anyone who has done this type of

research realizes its complexity, and it would be very easy for a researcher

to overwhelm the positive findings of a study with complications. Downplaying

the "why" was one way of avoiding these problems.

On the other hand, there was a group of items that appeared more than sporadically in kindergarten speech but were used from about three to ten times oftener by seventh graders. At various levels, there were significant increments in their use. These would appear good candidates for identification as generally later acquisitions. They were noun modification by a participle or participial phrase, the gerund phrase, the adverbial infinitive, the sentence adverbial, the coordinated predicate, and the transformation-produced nominal functioning as object of a preposition.The first paragraph supports the basic "that" conclusions mentioned previously, and it extends them into areas that will not be covered in this book. Coordinated predication (She read a book and then took a nap), for example, would be an interesting area for research. Some researchers have counted this as two separate main clauses, and others have reported conflicting results about when and how often they appear. It should be obvious, however, that such coordination may have a significant affect on main-clause length. The most interesting point in the quotation, however, is the parenthetical allusion to "formulas." Although I may have missed something, I have tried several times to find other references to this concept within O'Donnell's study, but with no success. This may be because the concept calls into question much of the statistical research of all three researchers. It is generally agreed (and a matter of common sense) that much of language is learned not as individual words, but rather as strings of words. This is obvious, for example, in idioms such as "It's raining cats and dogs." It is also apparent in many verbal phrases ("Wake up." "We get along.") Formulas are thus an aspect of vocabulary, but they are also an aspect of syntax. Syntactically, for example, some tenses are probably learned as formulas. Children repeatedly hear, for example, such things as "You are going to the store." "They are talking on the phone." "We are playing a game." What they learn from this is a syntactic string -- "___ are ___ -ing" into which various pronouns (and, of course, nouns) and verbs can be inserted. We can also see it, for example, in young children's use of some "subordinate" clauses. These children hear "when ___ get(s) ___" dozens of times, and probably pick this up as a string, i.e., a formula. If I understand O'Donnell correctly, he is implying that such formulaic expressions do not represent cognitive mastery of the underlying syntactic construction. The concept is very important and deserves much more research because it complicates research on natural syntactic development. Highly influenced by transformational grammar, O'Donnell believed that he was counting sentence "transformations" that result in more mature writing. One of the things he counted was coordinate constructions within T-units. (69) As a simple example of this, we can look at a simple compounding which probably does reflect syntactic growth. A very young child might say, "Mommy went to the story, and daddy went to the store." An older child is more likely to say, "Mom and dad went to the store." The transformational rules involved are complex and may differ depending on which transformational grammar one wants to use. We can easily see, however, that the more mature version involves deleting the repetitious "went to the store," and embedding the second subject into the first main clause. Thus, some compounds are clearly reflections of growth. But would anyone want to suggest that the compounding in It's raining cats and dogs is? Even in adults' writing, formulas are probably very frequent. They are certainly relevant to any analysis of the writing of college students. In a short essay discussed at the end of Chapter Nine, a college student used "reach out and touch it" three times. But anyone who is familiar with old AT&T commercials knows that no mental transformations produced the three compounded infinitive phrases. Just how damaging formulas are to the research of Hunt, O'Donnell, and Loban is impossible to tell. All the researchers give some examples of what they are counting, but transcripts of the students' writing are not available for review. O'Donnell, for example, gives "man outside" as an example of a transformation that was apparently counted (58), and from one point of view we can see why he would do so. "Man outside" is comparable to "bird in the tree," which O'Donnell discusses in the passage quoted above. We can look at "man outside" as a reduction of "man who is/was outside." It is much more likely, however, that children master this phrase as a formula. They are likely to frequently hear things such as "It's just the dog outside," and "It's the boy outside the store." The problem of formulas raises still another one. Perhaps because of their lack of a theory, the researchers counted all transformations as basically equal. There are, for example, numerous and complex transformations involved in creating the various forms of verb tenses. In that he briefly discusses them (19) but does not count them, O'Donnell suggests that some developmental transformations are more important than others. But he does not explain why, and he does not extend the idea of relative importance to the other constructions that he counts. I attempt to deal with this problem in more detail in the section on Theory, but here I want to suggest that transformational sequences that students are learning pose a great deal of difficulty, whereas transformational sequences that have been learned pose almost none. Thus, for example, once students have mastered the transformations that create verb tenses, these transformations become automatic. Because they no longer have to focus on these transformations, students are able to attend to others, gradually adding more and more constructions to their automatic inventory. A simple count of transformations, therefore, remains problematical without further consideration of both formulas and the relative sequential difficulty of the transformations. Having noted the problems presented by formulas, I would still suggest that the fundamental conclusions of Hunt, O'Donnell, and Loban are valid. Indeed, I would suggest that further investigation of formulas will resolve some of their problems. In his "Conclusions and Implications," O'Donnell asks if it is possible to define a sequence in children's acquisition of a productive repertory of syntactic structures. Having noted that a general kind of sequential development has been "indicated" in very young children, he asks if further evidence can be found relative to school age children. He prefaces his response with the following: This investigation offers no simple, direct answer to that question. If some item of syntax had been found absent in the speech of younger children but present in increasingly frequent use in more advanced grades, it would have seemed evident that it was a characteristically later acquisition. No such instance was observed. (91)He then goes on to suggest the possibility of advanced constructions (discussed above), in the process of which he alludes to formulas. He seems to miss the very real possibility that formulas may account for most, if not all, of the "advanced" constructions in younger children's language. This is particularly possible because one cannot separate a purely syntactic description of children's writing from the semantic and from their conceptual abilities. As Vygotsky noted, The child may operate with subordinate clauses, with words like "because," "if," "when," and "but," long before he really grasps causal, conditional, or temporal relationships. He masters syntax of speech before syntax of thought. Piaget’s studies proved that grammar develops before logic and that the child learns relatively late the mental operations corresponding to the verbal forms he has been using for a long time. (Thought 46)It is very possible, therefore, that the subordinate clauses, appositives, participles, etc. in the writing of most pre-seventh graders are formulaic. Thus far, I have discussed formulas in the context of the research, but they may be very important in what and how we teach. I know I am not supposed to, but I will admit that sometimes I drink coffee while driving, especially on long trips. Sometimes, while driving, I even fill my coffee cup from my thermos. I can do this, with care, because I have been driving for more than thirty years. Driving has become automatic. If I had tried to drink coffee while I was learning to drive, my driving instructor would have told me to pull over and have gotten out of the car. He would not have wanted to be in the almost certain crash. Because syntactic development takes place in students' brains, where we can't see it, we tend either to not see, or to ignore, all the possible hazards. Formulaic expressions in students' writing and speech often deceive teachers into thinking that their students understand advanced constructions when, in fact, they do not. Many teachers, for example, claim to have seen participles, appositives, etc. in the writing of their young students, and thus claim that their students can understand and will be helped by grammatical explanations of these constructions. But when they are asked if what they saw might be formulas, these teachers have usually never even heard of the concept. Attempting to force advanced, "late-blooming" constructions into the writing of students who are not ready for them may cause mental confusion and crashes. These crashes may be just as, or even more serious than, the crash I certainly would have had if I had attempted to drink coffee while just learning how to drive. In this respect, Loban's study is particularly important. The graph given above is just one of many that demonstrates significant differences between advanced and slower students. The advanced constructions that teachers claim to see may just be in the writing of these students. If that is the case, the advanced students don't really need more help, especially if that help comes at the cost of confusing the less advanced students. If the constructions appear in the writing of the weaker students, they are probably formulas. As noted in the previous chapter, Hake and Williams suggest that sentence-combining exercises, for example, are effective only when students are ready for them. "Late-Blooming" Constructions Throughout this chapter I have suggested

that these researchers have shown that some grammatical constructions develop

later than others. The general outline of that development appears to be

1) the development of basic sentences through sixth grade, 2) the blooming

of subordinate clauses in seventh and eighth grades, and 3) the late blooming

of constructions such as the gerundive and appositive. Hunt was the researcher

who explored and expressed this sequence the most clearly and forcefully.

The science of measuring syntactic maturity is barely emerging from the stages of alchemy. It scarcely deserves to be called a science at all. But we do know a few things.Hunt's focus is clearly on "measuring," but do I detect in that last paragraph a caution against rushing natural syntactic development? He immediately turns to examining some sentences: Let us look at some fourth-grade writings. We find pairs of main clauses like this:After giving about a dozen more examples, he uses them to explain the "subordinate clause index." That done, he refers to the research of O'Donnell and others to conclude that From the first public school grade to the last the number of subordinate clauses increases steadily for every grade.As the graph from Loban (above) indicates, this turned out to be an oversimplification, but we need to keep in mind Hunt's purpose here, and his non-technical audience. We should also note that this article precedes the massive focus on sentence-combining, massive in the sense that entire classes were subjected to such exercises, often with no regard to what grammatical constructions their teachers saw in the students' writing. Having explained that, among subordinate clauses, adjective clauses are the best measure of maturity, he continues: But of course subordinating clauses is not all there is to syntactic development. In every pair of examples I have given so far, it would have been possible to reduce one of the clauses still further so that it is no longer a clause at all, but merely a word or phrase consolidated inside the other clause. In this fashion two clauses will become one clause. The one clause will now be one word or one phrase longer than it was before, but it will be shorter than the two clauses were together. By throwing away some of one clause we will gain in succinctness. The final expression will be tighter, less diffuse, more mature. (734)Now remember that my argument here is that Hunt, particularly at this point in his career, is just counting. His numbers, moreover, may be suspect. But the examples that he gives are extremely significant, particularly because of the range of constructions involved . He notes "A clause with a predicate adjective can all be thrown away except for the adjective." (734, my emphasis) He then gives two examples. One of his original examples of fourth grader's sentences was "One upon a time I had a cat. This cat was a beautiful cat. It was also mean." Previously he had suggested that this could be rewritten as "Once upon a time I had a cat who was a beautiful cat. It was also mean." Here, he suggests that it can also be rewritten as "Once upon a time I had a beautiful, mean cat." Another of the original examples was "The jewel was in the drawer. It was red." Having suggested that it could be rewritten as "The jewel which was red was in the drawer," he now suggests "The red jewel was in the drawer." Having given two possible "revisions" of the original sentences, Hunt does not suggest that one may be more "mature" than the other. He simply notes that "Eighth graders write more than 150 percent as many single-word adjectives before nouns as fourth graders do." (734) He then turns to some of the originals which could have been combined by using a simple prepositional phrase: "If a clause contains a prepositional phrase after a form of be you can throw away all but that prepositional phrase." (734) To demonstrate this, he gives another version of the "jewel" example -- "The jewel in the drawer was red." His other example here does not match the original, but it still makes his point. His original example was "Today we went to see a film. The film was about a white-headed whale. (which was about a white-headed whale.)" Here he gives "Today we saw a film about Moby Dick." And he notes that "Eighth graders use such prepositional phrases to modify nouns 170 percent as often, and twelfth graders 240 percent as often, as fourth graders do." (734) Next, he shows how "have" can be transformed into a genitive: "If the clause contains a have you can often put what follows the have into a genitive form and throw away the rest. His original example (and subordinate clause alternative) was "I have a new bicycle. I like to ride it (which I like to ride.)" Here he suggests "I like to ride my new bicycle." His other example was -- in the original -- "We have a lot on Lake Talquin. This lot has a dock on it. (On Lake Talquin we have a lot which has a dock on it.)" He now proposes, "Our lot on Lake Talquin has a dock on it." He notes, "Twelfth graders used 130 percent as many genitives as fourth graders do." (734) He immediately turns to appositives: "If a clause contains a predicate nominal, it can become an appositive, and the rest can be thrown away." "There was a lady next door who was a singer" can be written as "There was a lady next door, a singer." (734) He gives two more examples of this: 1) "His owner was a milkman. The milkman was very strict to the mother and babies. (who was very strict . . .)" becomes "His owner, a milkman, was very strict to the mother and babies." 2) "One day Nancy got a letter from her Uncle Joe. It was her great uncle. (who was her great uncle.)" can become "One day Nancy got a letter from her great uncle Joe." Having simply noted that "Eighth graders wrote a third more appositives than fourth graders," he immediately turns to what KISS calls the gerundive: " Often clauses with non-finite [non-linking"? EV] verbs can all be thrown away except for the verbs, which now become modifiers of nouns." (735) He gives two examples, the second with two possible variations: 1) "Beautiful Joe was a dog, he was born on a farm. (that was born on a farm.)" can be written as "Beautiful Joe was a dog born on a farm." 2) "One colt was trembling. It was lying down on the hay. (One colt which was lying down . . .)" can be written as either "One trembling colt was lying down on the hay" or as "One colt, lying down on the hay, was trembling." He notes that "Eighth graders wrote 160 percent and twelfth graders wrote 190 percent as many non-finite verb modifiers of nouns as fourth graders did." (735) I have quoted all of Hunt's examples because we need to look at both the positive and negative sides of what he was doing. On the positive side, Hunt states his purpose very clearly: I have used this set of examples twice now, to show two different things: first, how it is that older students reduce more of their clauses to subordinate clause status, attaching them to other main clauses; and secondly, how it is that the clauses they do write, whether subordinate or main, happen to have more words in them. (735)Most readers would probably agree that he has successfully made his point. He then goes on to explain that the reductions are improvements in style because the words that are "thrown away" are insubstantial. He has also demonstrated a variety of grammatical ways in which these reductions can occur. Since he is interested in proving that reductions occur and that their appearance is a good thing, he never suggests that his examples of the ways in which they occur are exhaustive, nor does he suggest that some of these ways may be more difficult than others. In turning to the negative side of this article, I need to note that I am asking for more than what Hunt himself claimed to be trying to give. Hunt was, however, so close to a theory of natural syntactic development that we need to look at what he was missing. One of the more interesting aspects of the article is that Hunt discusses the alternatives (subordinate clauses and non-clausal versions) almost as if they are developmentally equal. Is he suggesting, for example, that an eighth grader has an equal option between using a subordinate clause and using an appositive? He never makes this clear. He does describe the embedding of each example as a subordinate clause first, and then demonstrates that each can be further reduced to a non-clause. But if I understand it correctly, this was a basic principle of the transformational theory that Hunt was using. Kernel sentences (basically, the sentences written by the fourth graders) are first embedded into another sentence, and then reduced, either to subordinate clauses or to non-clausal constructions. It is possible, therefore, that Hunt was simply following transformational theory, and was not suggesting, in this article, a sequence of development beyond the subordinate clause. A similar problem appears within the discussion of the less-than-a-clause reductions. The numbers he gives suggest that some of these reductions are used less frequently than others, but the way in which he presents the numbers makes the question obscure. "Percent of increase" can be deceptive. Eighth graders, he noted, "use such prepositional phrases to modify nouns 170 percent as often, and twelfth graders 240 percent as often, as fourth graders do." This can mean that the fourth graders used this construction 100 times, the eighth graders 170 times, and the twelfth graders 240 times. On the other hand, when he stated that "Eighth graders wrote a third more appositives than fourth graders," it may mean that he found three appositives in the writing of fourth graders, and four in the writing of eighth graders. Whether intentionally or unintentionally, the numbers were presented such that they obscure the question of relative difficulty and frequency. In addition to that, Hunt ignores the problem of formulas. Is "great uncle Joe" a true appositive (one formed by embedding and deletion), or is it a formula? Hunt was, I am sure, aware of the third "problem" with his presentation in this article. Embeddings and deletions which result in compound subjects and verbs were recognized early by all these researchers. A fourth grader is likely to write, "Sally went swimming. And Molly did too." By eighth grade, this is much more likely to be expressed as "Sally and Molly went swimming." The fourth grader's "We played baseball. Then we went to dinner," will, by eighth grade, probably be expressed as "We played baseball and then went to dinner." I have mentioned this "problem" only to set the background for explaining another, and major contribution of Hunt's, a contribution that is suggested in the variety of reductions that he covered in this article. One of the things that all these researchers noted is that syntactic development is "glacially" slow. In attempting to determine what happens, i.e., what changes occur, they had little time to explore why. Hunt, O'Donnell, Loban -- all noted that in seventh or eighth grades subordinate clauses blossom, but none of these researchers ever explained in any depth why they don't blossom sooner. If we shift our perspective from what happens to where and how it happens, Hunt's list of reductions to less than a clause becomes very suggestive. We need to put the sentences that Hunt discusses back into a context. No student ever writes simply "The jewel was in the drawer. It was red." These sentences were written as the student attempted to write a story or paragraph to convey ideas that were in his or her head. This particular sequence of sentences gave Hunt the opportunity to use them as an example of how the second could be combined into the first, but how often does this opportunity occur in the writing of fourth graders? My experience with the writing of fourth graders is limited, but from what I have seen, they have a tendency to write two, three or four sentences on a topic, and then jump to a different topic. The opportunities would have to appear within the discussion of a specific topic, and frequently what they write presents few useable opportunities. Note that Hunt is clearly suggesting that fourth, fifth, sixth, etc. graders automatically (no instruction involved) begin to make such combinations. They may do so unconsciously (in their heads) and/or consciously, i.e, they may write it out as two main clauses and then consciously revise. Hunt was also well aware of the distinction between competence and performance. A fourth grader may well be competent to make this combination, but simply opt not to do so. Writing involves a lot more than just making longer, more complicated sentences. In his attempt to show that such embeddings and reductions occur, Hunt gave a number of types of examples, but, as noted above, he does not even begin to suggest that his list is comprehensive. There are, in other words, probably many more ways in which the important information in one "base" clause can be embedded into another simple main clause. Fourth graders thus have numerous possible ways of combining -- in the context of real writing, writing which presents relatively infrequent opportunities for each such combination. Students, moreover, may or may not opt to use them, even if they are competent to do so. It has sometimes been suggested that in fourth grade students learn how to write basic clauses; in seventh and eighth, they learn how to subordinate clauses. In between the two, they goof off. But that is not the case. Hunt's list of types of reductions suggests that massive growth may be occurring in these years, but that we simply haven't seen it because we haven't known what to look for. We need to keep this in mind before we try to get pre-seventh graders to increase the frequency of subordinate clauses in their writing. There is much more that can be said about Hunt's "Recent Measures in Syntactic Development," some of it positive, some negative. But the article is short and not very technical. I strongly suggest that anyone interested in the details of syntactic development should read it. I have probably already gotten too far ahead into KISS theory, but I have done so to demonstrate that Hunt was already so close to it. He was even closer in a later article. In 1977 he published "Early Blooming and Late Blooming Syntactic Structures" (in Cooper and Odel, eds. Evaluating Writing. NCTE, 1977. 91-104). Like "Recent Measures," it is short, easy to understand, and very important for anyone interested in natural syntactic development. Unlike his earlier and most famous study, the study reported in "Blooming" involves what Hunt calls "rewriting" as opposed to "freewriting." Whereas for the earlier study he had simply collected samples of whatever the students were writing about for school, in this "rewriting" study participants were given the "Aluminum" passage and asked to rewrite it. The "Aluminum" passage is written in very short sentences. Hunt includes the entire passage at the end of the article, but he discusses the first six sentences: 1) "Aluminum is a metal." 2) "It is abundant." 3) "It has many uses." 4) "It comes from bauxite." 5) "Bauxite is an ore." 6) "Bauxite looks like clay." In explaining the advantages of the passage as a research tool, Hunt notes that "since all students rewrite the same passage, all students end up saying the same thing -- or almost the same thing. What differs is how they say it. Their outputs are strictly comparable." (92) To demonstrate this, Hunt gives three rewritten examples. Typical output of a fourth grader:The passage can be an excellent research tool. Unfortunately, Hunt was, by this time, himself somewhat caught up in the sentence-combining frenzy, so he missed some of the problems with it. Often overlooked, but perhaps one of the most important aspects of this article is that Hunt, all by himself, partially closes the "gap" that had led to the "race-horse" studies and the subsequent emphasis on sentence combining without instruction in grammar. Hunt was, of course, himself largely responsible for the gap -- his studies had demonstrated the wide gap between 12th graders and "superior adults." You may have noted that his earlier "Superior Adults" has now become "Skilled Adults." Hunt was able to get rewrites from twenty-five "authors who recently had published articles in Harpers' or Atlantic." (96) These are his "Skilled Adults." But he added a group between these skilled adults and the 12th graders: "twenty-five of Tallahassee's firemen who had graduated from high school but had not attended college rewrote the passage too. They will be called average adults." (96) To reinforce the validity of his previous work, Hunt turns to words per T-unit and gives the figures for grades four, six, eight, ten, twelve, for the average adults, and for the skilled adults. The figures are 5.4, 6.8, 9.8, 10.4, 11.3, 11.9, and 14.8. He then states, "Notice that average adults are only a little above twelfth graders, but skilled adults are far above both groups." I have already discussed the problems with this gap, so here I will simply suggest that the gap might close still more if we knew more about the high-school students (How many of them graduated?) and about the firemen (How many of them had had advanced, but non college education?) Remember also that in using the edited articles from Atlantic and Harper's, Hunt had arrived at a significantly higher 20.20 words per main clause for the "Skilled Adults," and a gap of almost six words between them and the 12th graders. Here, that same gap has dropped to 3.5 words. It is somewhat ironic that Hunt was closing the gap that started the rush towards sentence-combining at the same time that he himself was getting caught up in the rush. Perhaps because of space limitations, "Early Blooming" is a bit confusing. Although it is primarily about the "Aluminum" passage, Hunt discusses the revision of another, ("Chicken") passage, and he ends up scrambling the results from revision of both, including the university students' revisions of the "Chicken" passage. Like all these research reports, this one is crammed with data and ideas which fascinate those of us who are interested in the problem. Here, however, I have to limit myself to two of what Hunt considers the middle and later blooming constructions. The first of these is the appositive. Hunt states that "Ability to write appositives was in full bloom by grade eight, but not by six or four. Here is the number of appositives produced by successively older grades: 1, 8, 36, 30, 34." (98) I would suggest that Hunt has a problem here. Fundamentally cautious, earlier in the article he notes that There is, of course, a danger in generalizing from a single rewriting instrument. The results obtained will depend to some extent on the problems set. Insofar as the investigator sets an abnormal task he or she will get an abnormal result. These results need to be checked against free writing." (92)First of all, the results that Hunt gives for appositives are all from the rewritings -- there is no check against freewriting. Second, as Hunt himself notes, the "Aluminum" passage gives students four opportunities for creating appositives. Third, there were apparently 50 children in each grade level. (Hunt simply states that there was a total of 250 schoolchildren in the five grades.) This means that even with the 36 appositives for the eighth graders, we are talking about less than one per student, and remember that there were four "invitations" for each student. The fifth problem is related, in part, to the fourth -- if the appositive is a sign of maturity, why does the number decrease for tenth and twelfth graders? And why doesn't he give us the numbers for the average and skilled adults? And finally, sixth, there are some problems with the "Aluminum" passage as a research tool that are not well understood. I noted previously the significant decrease in words per main clause between the skilled adults' rewritings of the "Aluminum" passage and their articles in Atlantic and Harpers'. I have also done a fairly complex study with the passage myself. (Available on the KISS web site, it provides a detailed analysis of rewritings by 93 college Freshmen.) Although I was not able to include the analysis of my students' freewriting in that study, I noted a very significant, similar difference in words per main clause. Whereas my Freshmen (as a group) usually average very close to 15 words per main clause, in rewriting the "Aluminum" passage, they averaged only 10.7. Clearly there are some major psychological differences between rewriting someone else's sentences and creating a text oneself. If the preceding cautions seem excessive, we need to remember what we are discussing here. We are talking about meddling with our students' minds, minds which Mother Nature develops naturally and, generally, beautifully. Disappointingly, from my perspective, Hunt in this article talks about sentence-combining in the elementary grades as a good way to improve students' writing. (102) Mellon, in his paper at the conference discussed in the preceding chapter, stated that "Sentence combining produces no negative effects . . ." (35) The final words of his presentation were "the best advice I can give teachers today, relative to sentence combining, is -- Do it!" (35) The problem with this, and perhaps the main reason that sentence combining has lost its initial charm, is that it should be done with an eye on natural syntactic development. There are probably major differences between giving eighth graders combining exercises in which they create subordinate clauses, and giving them exercises that necessitate appositives. There is certainly a difference between following and supporting Mother Nature, as opposed to forcing her. Whereas I have suggested caution about Hunt's conclusion relative to eighth graders and appositives, I would suggest that his data can be interpreted more forcefully in a different way -- fourth and sixth graders are clearly not ready for instruction in appositives. Given 200 invitations each (50 students times 4 invitations per student), they produced only one and eight appositives respectively, and even here, without the transcripts, we cannot be sure that the appositives that they did produce were not formulas. The NCTE resolution against the teaching of grammar demanded theory and research, but what good are theory and research if we do not use them to guide our instruction? The other important late-blooming construction is the gerundive. Interestingly, Hunt does not give it a name, referring to it instead as "this construction," and identifying it with an example from Christensen, who took it from E.B. White: We caught two bass, hauling them in briskly as though they were mackerel, pulling them over the side of the boat in a businesslike manner without any landing net, and stunning them with a blow on the back of the head.Hunt reports that of the 300 people who rewrote "Aluminum," "not one of them produced this construction." (my emphasis) In that this includes both the average and the skilled adults, this is an odd finding. In examining the revisions by my college students, I found that more than half of them produced the construction. Some examples are: "It comes from an ore that looks similar to clay called Bauxite." and "To finally produce the metal, the workmen seperate the aluminum from the oxygen using electricity." One has to wonder why it was not used at all by any of the 25 skilled adults. Perhaps because no one used it for him, Hunt here switches to a discussion of the "Chicken" passage. He states: Out of 10 fourth graders who rewrote "The Chicken," not even one produced it. By 10 eighth graders who rewrote it, it was produced once:The gerundive is a late-blooming construction -- perhaps as late as college. Near the end of the article, Hunt does suggest the application of the "blooming" sequence to teaching. "The kind of information given previously as to which structures bloom early and which bloom late would be preliminary to actual measures of teachability at a given level." (102) This sentence is never developed and has been ignored. Thus we have sentence combining exercises for second graders in which they are required to use appositives, and even, in some cases, gerundives. Hunt was, as I suggested at the beginning of this section, very close to the KISS theory of natural syntactic development. In fact, he was extremely close. In Part Two of this book, we will see just how close, but first we need to address the (lack of) development of Hunt's theory and the problems of additional research. The Death of the Research I am often asked if there is research

on natural syntactic development that is more current than that of Hunt,

O'Donnell, and Loban. When I say that the answer is basically "No," I am

asked "Why?" To answer both questions, we really need to go back and ask

why the research on natural syntactic development exploded into the scene

in the 1960's. There are probably two reasons for that -- money and Hunt.

All of the major studies cost money. After the Soviet launch of Sputnik

in 1957, the Federal government, as well as various foundations, poured

waves of money into education for math and the sciences. The push for new

ideas in education, of course, also affected the Humanities, and thus more

money than usual was available for research in English. Grants were relatively

easier to get. Among others, Hunt got some. Grants are more likely to be

renewed, or other grants are more likely to be obtained, if one's initial

grants result in something productive. As should be obvious by now, Hunt's

original projects were certainly productive. They led to numerous

other educators wanting to build on Hunt's work, especially in an attempt

to close that terrible gap between 12th graders and superior adults. A

gap that wide was clearly visible, even to our politicians. Thus, more

research was supported.

Is Decent Future Research Possible? Anything, of course, is possible. Naturally

I have some suggestions. (What did you expect?) For one thing, any credible

future research projects should make transcripts of the speech or writing

samples available on the internet. Throughout this and the preceding chapter

I have regularly referred to the problems involved in evaluating previous

research because we do not have such transcripts. The different ways in

which concepts are defined, the differences in what is counted (or thrown

out), and the problem of formulas -- all make any study highly suspect

unless these transcripts are available for review (and further research).

Previous researchers, of course, had no way of making such transcripts

economically available, but the advent of the web makes their storage and

transmission a very simple matter. A major educational organization (NCTE?)

should be persuaded to serve as a well-publicized home for this data. (Imagine

what could be done if the transcripts from Loban's students were available

on the net -- thirteen years worth of writing samples from the same students,

divided into three distinct ability groups!)

Take a break. Theory is next. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This border presents (French, 1755-1842) 1803, Indiana University Art Museum [for educational use only] |